A Laboratory Focus Appears in Royal Infirmary Medicine

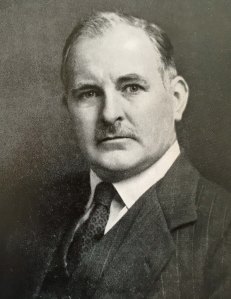

Leslie John Davis initially trained as a research medical scientist at the Wellcome

Bureau of Scientific Research. Thereafter he was appointed to the staff of the Wellcome Tropical Research Laboratories in Khartoum and practiced laboratory and clinical medicine there from 1927 to 1930. Davis then became Professor of Pathology at Hong Kong University from 1931 to 1939 but left before the outbreak of hostilities. After a short spell as director of medical laboratories in Bulawayo in Southern Rhodesia, he returned to Edinburgh during the Second World War as an assistant and then lecturer in the Department of Medicine to work in medicine and haematology with Stanley Davidson (later Sir Stanley).

In 1945, Davis was appointed the third Muirhead Professor of Medicine in the newly formed University of Glasgow, Department of Medicine (UDM) at the Royal Infirmary (GRI). It is likely that the Principal Sir Hector Hetherington and the Medical Dean George Wishart saw in Davis, an opportunity to modernise East Glasgow hospital medicine and bring into the hospital, a research programme based on sound scientific and academic principles introducing laboratory methods into clinical medicine as well as maintaining the reputation of the UDM at Glasgow Royal Infirmary for first class clinical practice and teaching. The closure of the Saint Mungo’s College building provided Davis with all the accommodation required to set up a laboratory based Department of Medicine adjacent to the Infirmary. The St Mungo College building had been the base for the St Mungo’s Medical School which had opened in 1888 and only closed in 1945 along with Anderson College on Dumbarton Road following a report from the Goodenough Committee which recommended closure of all extra mural medical Colleges. Davis was therefore able to attract young medical graduates to his Unit who had the desire to apply science to clinical practice. Around nuclei of clinical research programs, young researchers were attracted by the buzz and the energy of the Unit and their involvement in clinical teaching. Funding for these young researchers at GRI was usually found from Hall Fellowship, McIntyre or Ure Research Scholarships and were keenly contested.

As the first full-time University of Glasgow Professor of Medicine at GRI, Davis began transforming his new department into a teaching and clinical research facility by appointing his senior lecturers strategically.

His senior appointments were Alex Brown his deputy, Edward McGirr, Stuart Douglas, Jim Ferguson and Alex McFadzean. Tom McEwan provided the NHS focus. His juniors included Arthur Kennedy, Stuart McAlpine, Albert Baikie, Robert Pirie, Robert Hume, Jock Adams, William (Willie) C Watson and George P McNicol.

Despite a lack of broad clinical experience, Davis forged a centre of excellence in academic medicine at the Royal Infirmary. His strong background in Pathology meant that his own specialty interests lay mainly in Haematology which was the predominant activity of the UDM during his tenure of the Chair of Medicine. He published work and co-authored a book on megaloblastic anaemias with Alex Brown and worked on nitrogen mustard therapy for lymphoma. Davis regularly published on haemopoietic drugs and treatments and surveyed both the ESR in clinical practice but also the educational value of the classical medical history. He quickly became recognised as a first class clinical haematologist and by his careful choice of appointments, established a reputation of his University clinical unit for excellence in clinical practice and teaching. Davis’ laboratory-based department of medicine in the Saint Mungo College allowed him to use his experience to mentor his staff on the application of scientific skills to clinical practice and research. He gradually transformed a mainly clinical hospital into one favourable to laboratory-based research, clinical innovation and sub-specialisation.

LJ, as he was known by, retired in 1961 aged 60, moved to Yarmouth and, being keen on sailing, signed on with the Royal National Lifeboat Institution to help crew the local lifeboat.

Professor Davis died in 1980.[1][2]

Development of Specialist Academic Medicine

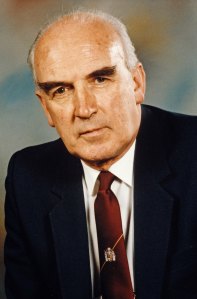

Edward McCombie McGirr. CBE, D.Sc., a Glasgow graduate with B.Sc in 1937 and MB (Hons) 1940, joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and served in India with rank of major until demobilisation in 1947.

He obtained his MRCP in India while on active service on the advice of Max (later Sir Max, then Lord) Rosenheim and also spent time in Thailand. Professor Davis appointed him on the recommendation of Professor John (later Sir John) McNee (Department of Medicine, Glasgow Western Infirmary) initially as a Clinical Assistant in Medicine within the fledgling UDM in 1947 and a few months later, as registrar at the same time as Dr Alex McFadzean (Brunton prize winner of his year) who later became Professor of Medicine in Hong Kong in 1950.

McGirr shared the lecturing and teaching of medical students, took responsibility for the dental student lectures, and shared the general medical responsibilities on wards 2 and 3 on first floor medicine at GRI and in ward A3 at Eastern District Hospital, Duke Street. The Eastern District Hospital had been built in 1904 as an acute hospital and was the first in Scotland to have a psychiatric assessment unit attached. At this time, the hospital medical wards were really pre-discharge wards though the psychiatric unit had enlarged and represented the mental health beds for GRI.

McGirr almost certainly would have been aware of the groundbreaking work reported in 1938 by Saul Hertz, Arthur Roberts and R D Evans[3] where the first ever biokinetic study of radioactive iodine-128 was performed in rabbits and the Hertz and Roberts reports on the first use of cyclotron produced radioactive iodine (90% Iodine-130 and 10% Iodine 131) in the treatment and investigation of patients with thyrotoxicosis in 1946. The confirmatory study by E M Chapman and R D Evans in similar cases and the work of S M Seidlin, L D Marinelli and E Oshry when the first therapy doses of radioactive iodine were given to patients with thyroid carcinoma confirmed that thyroid investigation and therapy had changed irrevocably. Observing these medical publications from the United States supporting the use of new cyclotron and later on, reactor- acquired radioisotopes of iodine when their production was de-classified in 1947, McGirr quickly realised that Medicine, and especially thyroid disease, could be transformed by the application of these exciting, scientific, technological and pharmacological advances to the study, investigation and treatment of disease.

Funded by the GRI, he immediately started training in the biology of radioactivity at one of the early courses at the Royal Postgraduate Medical School in Hammersmith, London and with this, began a lifelong passion for the use of radioisotopes to facilitate medical diagnosis, treatment and research.

Following a year’s sabbatical with Prof J B Stanbury at Harvard University, Boston in 1950, he returned to Glasgow and was able eventually to perform innovative and classic laboratory work on the aetiology of familial goitrous cretinism in a family of tinker patients of Dr JH Hutchison, later Professor of Child Health and with Dr Elspeth Clement, biochemist in the UDM who was responsible for much of the technical work. The pedigree of the tinker (gypsy) family extended over 160 years and revealed ten goitrous cretins. McGirr showed conclusively, in work that is still quoted and which took 6 years to complete, that enzymatic defects that caused dyshormonogenetic goitre were present in West of Scotland families. When a piece of thyroid tissue from one of them became available surgically, the biochemical defect was defined as deficiency of the enzyme iodotyrosine dehalogenase and revealed that it was transmitted as an incompletely recessive characteristic carried by an autosomal gene. This led to the award of MD with honours and The University of Glasgow Bellahouston Medal. It is interesting to note that Oastler and McGirr had both spent their sabbaticals at Harvard and each would have been been influenced by Saul Hertz, Oastler writing the important paper on the aetiology of hyperthyroidism with him in 1936 and McGirr being inspired by the many uses of radioactive iodine in thyroid disease in the early 1950s.

On return, McGirr was grateful for the sound guidance and support of his friend Sam Curran, nuclear physicist, later Sir Sam Curran, who had been a member of the Manhattan Project during the war and who had joined the Department of Natural Philosophy at Glasgow University in 1946. He later became Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Strathclyde.

Curran provided McGirr with a supply of radioactive sodium-24 which has β- decay with a half-life of 14.9 hours. He also provided him with his first Geiger-Müller counter to detect the beta particles externally. One of McGirr’s first publications in 1952 was on the clearance of this Na24 from ischaemic skeletal muscle and another on the effects of intermittent venous occlusion on this clearance. Although the technique appeared to have few clinical applications, it confirmed to McGirr that radioactivity was a safe tool which was going to change the face of medicine. He also attempted to investigate the vascularisation of skin grafts for Tom Gibson but again radioactive Sodium was unable to provide meaningful data.

Reactor acquired radioactive iodine -131 (131I) had remained classified after the war and it only became commercially available in the UK around the 1953-4. By that time, McGirr had acquired scintillation counters which enabled him to accurately measure the amount of the isotope in tissue and blood samples. The scintillation counter had been invented by Sam Curran in 1944 while he had been at the Radiation laboratory, Berkeley, California.

Concurrently, McGirr was developing a screening and diagnostic service for thyroid disease and polycythaemia and was helped initially by the GRI physicist, Walter Jackson. Later, the Regional Physics Department directed by Dr

JMA Lenihan, provided advice and assistance, supplied the radioisotopes and monitored staff exposure to radiation.

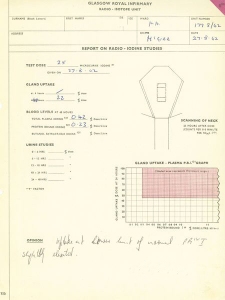

Using test doses of 131I, a 24-hour uptake of thyroidal 131I and a 48-hour protein-bound iodine (PB131I) were routinely performed on all patients. He also developed a procedure for labelling red cells with radiochromium to estimate blood volumes in polycythaemia and administered intravenous radiochromium for its treatment.

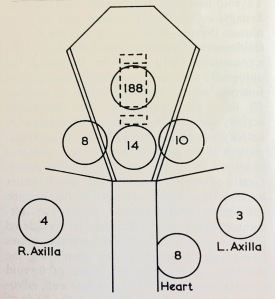

It was from this Department that McGirr published on the first ever patient where there was accumulation of radio iodine in the ectopic thyroid tissue in the tongue with an absence of uptake in the usual site (see Fig). In the early 1950s, McGirr also developed the GRI as a treatment centre for hyperthyroidism using the thionamide drugs developed by Professor Edwin B Astwood in Boston. He organised a thyroid outpatient clinic within the University Medical Unit (UMU) in the lecture room of ward 3, supported by the Radioisotope Department, to investigate the clinical value and effectiveness of these drugs. In addition, from 1954, he supervised and trained others in the early use of 131I for treatment of hyperthyroidism. This was to be the forerunner of the nascent speciality of Nuclear Medicine. With Drs Provan Murray and John A Thomson’s support, McGirr published one of the first series of 900 cases of hyperthyroidism treated with 131I in the UK in 1964.

On Prof Davis retiral in 1961, McGirr was appointed the fourth Muirhead Professor of Medicine. His department became one of the pioneers for establishing new specialities in Glasgow and for attempting new techniques. He himself was one of the few clinicians in the UK in the early 60s to see the potential for the rapidly developing field in which radionuclides were used to diagnose and treat human disease. He chaired a groundbreaking report on Isotope Services for the Scottish Home and Health Department in 1968 and chaired the First and Second Reports of the Intercollegiate Committee on Nuclear Medicine in 1971 and 1975. He became an influential supporter of Nuclear Medicine, as it was soon known, and was the British Nuclear Medicine Society’s Second President in 1969/70.

From 1961, when appointed to the Muirhead Chair, Edward McGirr gathered round him

individuals who were keen to expand the academic credentials of his Unit. As technologies improved, he fostered leaders and potential leaders in the medical specialities of Endocrinology (Drs Provan Murray and John A Thomson), Respiratory Disease (Dr F Moran), Nuclear Medicine (Dr W R Greig), Medical Computing (Tommy Taylor), Rheumatology (Dr W W Buchanan), and Clinical Haematology (Dr George MacDonald).

Those in Haemostasis and Coagulation (Dr Stuart Douglas), Gastroenterology (Dr W C Watson) and Renal Disease (Dr Arthur Kennedy) had already been appointed by L J Davis.

He managed to coordinate the efforts of these leaders of academic medicine yet held the reins loosely to avoid stifling what he recognised was the inevitable specialisation of hospital medicine. If LJ Davis were to be described as the father of academic medicine at the Royal Infirmary, then Edward McGirr could well be described as the father of specialist academic medicine since it prospered and developed quickly under his guidance.

Over subsequent years, McGirr gathered around him many young men and women with a similar passion for endocrinology and thyroid disease who each went on to contribute in areas of Endocrinology, Nuclear Medicine or both, either in the UK or abroad. He fostered them in practical ways and encouraged them to spend time in the USA to train further or learn new research techniques.

McGirr was a firm believer in the proverb ‘all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy’. He was aware that a happy Unit worked better than an unhappy one and was keen to reduce the load on juniors by trying new ways of working. Encouraged by his wife Diane who had trained as a physiotherapist, he would organise a Unit Ball once a year where medical staff and their wives, nursing sisters, ward nurses and technical staff could put on their glad rags and celebrate the passing of another year with one another in a relaxed social environment. This event was not to be missed and was usually a glamorous affair.

McGirr was admired by his junior staff, mentoring his young lecturers and Fellows formally when advice was sought and informally at coffee time in the staff room after the ward round. He was known to help individuals access the materials they required for their research. While McGirr could be a tough opponent to those who had their sights on the real estate of the UDM, he had a warm personality and when illness struck members of staff, he would enquire regularly on their health and for their recovery. If problems arose for his staff over which he had the power to influence, he usually made the attempt. One former member of staff recalls the UMU with McGirr at the helm as an ‘academic Camelot’.

McGirr was not afraid to venture into the arena of national politics and would contribute to ‘Standpoint’, an open forum for discussion of the local paper, The Glasgow Herald of the day. The issue of underfunding of the National Health Service and the effects of this upon medical staffing and the quality of the hospital environment for staff and patients appeared close to his heart. His most notable quotation was that ‘Life saving must take precedence over face saving’, a reference to the use of ‘Health’ as a political football. His most simple suggestion to the politicians – ‘a moratorium on change’.

He was an able ‘safe-pair-of-hands’ and this was quickly recognised within and beyond the University precincts.

McGirr was elected President of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow 1970-1972, and during this time, steered the College into the mainstream of national postgraduate teaching and examining by membership of the Joint Committee of Higher Medical Training 1970, Faculty of Community Medicine 1972 and the Common Final Part 2 of the MRCP UK in 1972. He became Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Glasgow in 1974 , Administrative Dean in 1978 and chaired many national bodies influencing health care and standards. He was latterly awarded both a CBE in 1978 for services to Medicine and an honorary DSc (Glasgow) 1994.

After retirement, McGirr kept contributing and published regularly in the Scottish Medical Journal becoming a philosopher, observer, historian and commentator on the politics of the Health Service and the history of Medicine.

Edward McGirr is remembered fondly as an accomplished and kindly physician, an intellectual and academic with a national and international influence, and a man with a friendly twinkle in his eye.

Professor McGirr died in 2003[3][4]

References

[1] ” Leslie J Davis: Obituary,” British Medical Journal, Volume 281, 29 November, 1980. Accessed November 20, 2017

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1714820/pdf/brmedj00049-0064.pdf

[2] “Leslie John Davis”: Lives of the Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians, accessed February 23, 2018.

http://munksroll.rcplondon.ac.uk/Biography/Details/1189

[3]. Saul Hertz, and the birth of radionuclide therapy

https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/33029717

[4]. “Professor Edward McCombie McGirr: Obituary,” accessed November 20, 2017.

[5]. “Professor Edward McCombie McGirr”: Lives of the Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians, accessed February 23, 2018.

http://munksroll.rcplondon.ac.uk/Biography/Details/5343

H W Gray

J A Thomson